by | Liz Alexander, PhD | Futurist. Author. Consultant. Speaker.

Dr. Liz Alexander has been named one of the world’s top female futurists. She combines futures thinking with over 30 years’ communications expertise to produce publications that showcase the advice of fellow futurists on issues including the future of education, and how businesses can practically benefit from working with the futures community.

Dr. Liz is the author/co-author of 22 nonfiction books published worldwide, that have reached a million global readers, and has contributed to leading US technology magazine Fast Company, Psychology Today, and journals such as Knowledge Futures, and World Futures Review. She earned her PhD in Educational Psychology at The University of Texas at Austin.

Our government should have acted with more foresight and clarity in telling the world and Japan what the (atomic) bomb meant,” theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer said after his “creation” was used by the U.S. to kill and injure around 200,000 Japanese civilians at Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II.

Similarly, Kamran Loghman, the inventor of weapons-grade pepper spray for law enforcement, was prompted in 2011 to lament the “inappropriate and improper use of chemical agents,” by campus police in California against UC Davis student activists.

While we can revel in the fact that human beings are creative problem solvers, we should also acknowledge that this talent frequently involves finding innovative ways to kill or maim each other. Nor should we ignore the fact that it is not just rogue states and terrorist groups that make use of biological weapons, a subset of what the World Health Organisation considers to be “weapons of mass destruction” and includes “microorganisms like virus, bacteria, fungi, or other toxins that are produced and released deliberately to cause disease and death in humans.”

We only have to consider the devastating effect of the novel coronavirus known as COVID-19—almost 84 million global cases and over 1.8 million deaths and counting (as of 2nd January 2021)—to see how lethal a deliberately deployed bioweapon could be in the wrong hands. Indeed, our global inability to control the ongoing pandemic is just one example of the unintended consequences of believing that we have total control over nature.

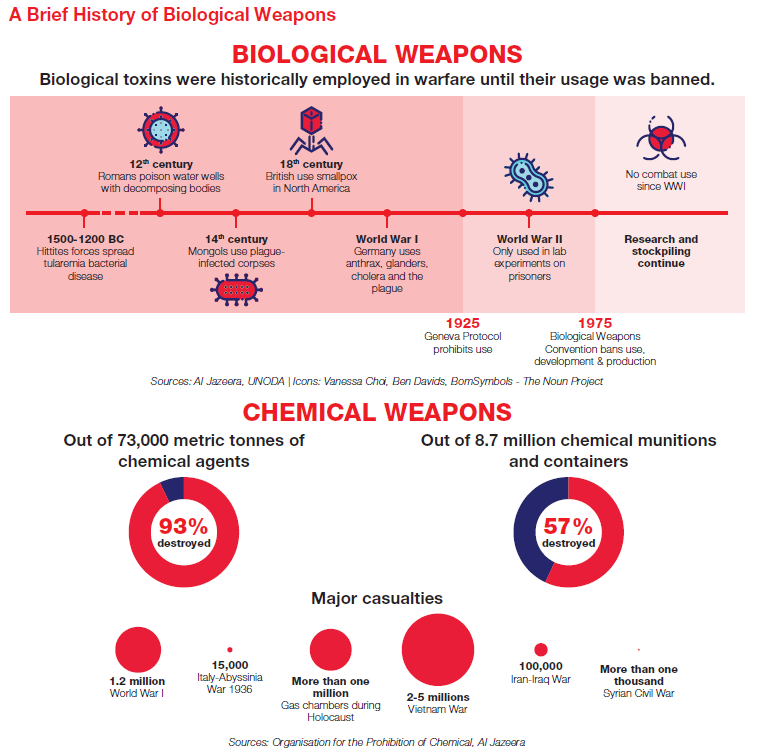

A Brief History Lesson

Human ingenuity with regards to biological warfare has a long and distasteful history. The English word toxic, meaning poisonous, comes from the Greek word toxikon, “pertaining to arrows or archery.” One early Greek historian wrote of how Scythian archers—who had a range of over 1,600 feet and could launch some twenty missiles a minute—would tip their arrows with what was likely a mixture of gangrene, tetanus, and poison from dead snakes, in order to incapacitate and kill their enemies during warfare.

Another ancient act of bioterrorism known as the Plague of Athens occurred during the Peloponnesian War during which the Spartans who were laying siege to that city were reputed to have infected the city’s water supply, possibly with fecal matter, resulting in the slow, painful death from typhoid fever, or blindness and dementia in the survivors. Nevertheless, the Spartan army sensibly withdrew when they saw the fires that burned the Athenian dead within the city walls, fearing that the disease would spread to their own camp.

Another historical occurrence of alleged biowarfare concerns the oft-disputed claim that during the French and Indian Wars (1754 to 1767), the British sent smallpox infested blankets to Native American tribes in order to annihilate them. Whether the plan was to bring about the tribes’ destruction or contribute to what is now being called “herd immunity,” contemporary writings show that the intention to infect was there. Captain Simeon, the commander of Fort Pitt, wrote somewhat ambiguously in his diary at the time: “Out of regard for them [two Indian chiefs] we gave them two blankets and a handkerchief out of the Smallpox hospital. I hope it will have the required effect.”

Millions in Germ War Tests

Any sensible, humane, and ethical individual would realise that once unleashed, biological weapons can never be contained to just ‘the enemy.’ A secret Japanese program known as Unit 731 employing some 3,000 scientists and technicians undertook ‘experimental infections’ of dysentery, cholera, and bubonic plague on Chinese prisoners, according to one article published by a U.S. professor of respiratory care and health sciences. He reported that when millions of infected fleas were released by the Japanese over the city of Changde in the Hunan province of China in 1941, it resulted “in nearly 10,000 cholera cases and 1,700 deaths” among the equally vulnerable Japanese troops stationed there.

In traditional warfare this kind of mishap is ironically called “friendly fire.” Yet sometimes countries deliberately use their own populace as experimental guinea pigs. In his 1989 book, Clouds of Secrecy: The army’s germ warfare tests over populated areas, author Leonard A. Cole—director of the Program on Terror Medicine and Security at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School—drew on declassified government reports and other testimonies to report that the U.S. Army, “…had been secretly spraying clouds of bacteria over populated areas in order to study America’s vulnerability to biological weapons.”

Unfortunately, and especially in the age of the Internet, information also spreads like a virus. In the same book, Dr Cole reveals that in the mid-1960s the U.S. released a non-toxigenic probiotic into the New York subway system to test how easily a biological organism could spread below-ground. Some have speculated that this knowledge may have inspired the release of the nerve agent sarin by non-state actors on the Tokyo subway system in 1995, leading to the deaths of thirteen people and seriously injuring fifty more. A toll that could have been much worse had the group behind the attack been more scientifically savvy. As Milton Leitenberg points out in his book The Problem of Biological Weapons , one unintended consequence of reporting—even exaggerating—the incidences of bioweaponry, is bringing such possibilities to the attention of rogue organisations.

Airborne Biowarfare and the Evolution of Values

Terrorist groups aside, one would expect responsible governments to come to an agreement that offensive biological inventions are “barbarous,” “abhorrent” and “criminal.” This occurred in 1972 with the UN Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological and Toxin Weapons and their Destruction (BTWC), which was reinforced in 1993. The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons was set up in The Hague to underscore to States “the huge potential for both good and harm that major advances in the chemical and biological sciences bring,” requiring “vigilance against the misuse of these advances.” Yet, even after signing the BTWC, the Soviet Union is said to have continued its offensive bioweapons program “into the 1990s .”

Loopholes in these conventions also exist and are exploited by countries including the U.S. As recent events there have shown, one person’s protest against racial injustice is another person’s riot. Consider “tear gas” for example, a chemical weapon that can be used legally as a tool to quell civil unrest, whether against one’s own citizens or at embassies on foreign soil that are under perceived attack. As news reports suggested, police used such “incapacitating chemical agents” against U.S. citizens who acted in a way the Trump administration did not like at Washington DC’s Lafayette Square and Portland, Oregon, offensively rather than defensively.

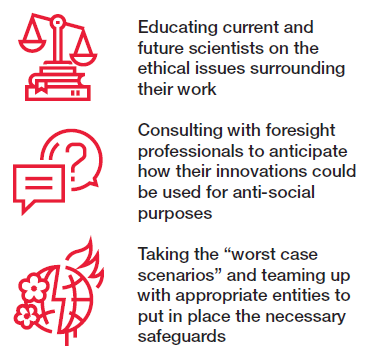

Hence, I’m not convinced that international agreements offer much of a solution. A more effective way would be to ensure that those within the scientific and technical communities accept both personal and collective responsibilities, especially those working at the cutting edge of bioweaponry, by:

Super Soldiers for the Future?

Unfortunately, as one author writing for the Journal of Strategic Security points out: “Many communities and governments choose not to plan for “worst case” scenarios to avoid costs and unnecessarily raising fear or concern among the population. However, the lack of planning is often what causes the most dollars, time and lives lost in the aftermath of a catastrophic event .”

Sadly, too, while it’s easy enough to outline what needs to be done, not everyone shares the same perspective. For every advancement such as giving brain implants to opioid addicts to help them overcome their substance abuse, there are reports of countries using CRISPR technology to create “biologically enhanced super-soldiers .” For every doctor who claims such beneficial brain implants “should not be used for augmenting humans,” there are military ethics committees that say such innovations are necessary to enhance military capabilities, not least “because everybody else is doing it.”

Just imagine what could happen if the “new cloaking skin” that is being developed in South Korea to help troops become “invisible,” even to heat sensors, gets into the hands of terrorists and criminals. I wonder if the scientists working on that project have thought of that—or even cared about it.

As one U.S. Navy officer told the media when asked about the wisdom of gene-hacking soldiers, “When we start playing around with genetic organisms, there could be unforeseen consequences .” I would offer a minor correction to that statement: There will undoubtedly be unforeseen consequences!